Cheeky Cocktails: cute on the shelf, ruthless in the build

How to build a mixers brand that feels premium, sells to pros and civilians, and is a lot more than "nice".

Cheeky Cocktails might look cute on the shelf, but the work behind the brand is not cute. It’s a story of building over time and putting in the work.

Its cool and cheeky.

Cheeky is a line of bar-quality cocktail mixers made with fresh juice and simple syrups, designed to give both bartenders and home drinkers a reliable, shelf-stable shortcut without preservatives.

When I sat down with founder April Wachtel, I admittedly expected to hear a classic founder story: “I saw X lacking, so I decided to make it!”

April’s story is far more nuanced, and real, than that (to be fair, most stories are, but maybe people just package them in the **fairy tale** way because they feel like they should? PSA: you don’t need to do that.)

This conversation was very frank and I loved it.

“The press loves beginnings and endings”

“I didn’t have an aha moment,” April told me. “The name ‘Cheeky’ just came one day after hundreds of wrong names.”

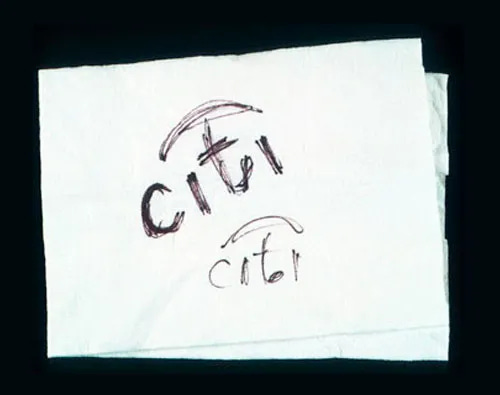

I laughed because I’d just brought up Paula Scher: the Pentagram designer who drew the Citi logo in minutes. When people questioned the price ($1.5m, allegedly), she said: “It took me a few seconds to draw it, but it took me 34 years to learn how to draw it in a few seconds.”

“The press loves beginnings and endings. But the reality is the messy middle. That’s what actually builds a brand.”

The brand focal point

Most founders at this stage will say they are investing heavily in packaging, PR or distribution. April’s answer was both blunt and simple. She invested heavily in one thing:

“The logo.”

“We spent so much money on that,” she says. “And that’s the only thing that we’ve ever spent money on, like a real amount of money. I knew if we got that one thing right, everything would be different.”

The logo became the anchor. We often talk about this with our clients at Nihilo Agency - there needs to be something that anchors your brand. If Cheeky were to change the bottles, or the labels, or pretty much anything else, but they kept the logo, it wouldn’t feel like a big deal. It would still feel like Cheeky. And that’s the point.

Essentially: one big bet and a moment of decisiveness created a backbone strong enough for the rest of the brand to stay scrappy….

Speaking to two audiences at once without alienating either one - impressive

Cheeky feels, well, cheeky. It’s a fun brand with a playful logo and fun colors. It doesn’t conjure up the intimidating nature of cocktail culture at all. I like that, and apparently I’m not alone.

“That was intentional,” April said. “Our labels explain simple syrup, but we also use bartender ratios like 1:1 or 2:1. The consumer feels like they can figure it out. And bartenders know right away this came from someone who’s worked service.”

Being able to speak to two VERY different audiences (consumers and bartenders) without alienating either one is very hard. Not only is Cheeky doing that, but they’re meeting people where they are: helping beginners, but making them feel like they can do it, too.

(I’m sorry the video quality lapsed here, but its still very interesting:)

It appears easy, but its not. Nice job, Cheeky.

Channels have different tones

In today’s ~~multimedia~~ world, there are many ways to talk to our audiences. Increasingly, those ways are online. So we talked platforms. I asked April how she thinks about splitting messaging between the trade (bartenders and the like) and civilians (the rest of us).

“I think if we want to create an aesthetic perception of our brand where it's super elevated, we can create that holistically on Instagram… TikTok is where we actually show real personality – BTS stuff and goofy whatever… and the trade just wants the most bare bones real talk.”

I love that division. One channel doesn’t have to do do everything, and developing a proper, individual strategy for these different platforms is rarer than you’d think (go on Insta or TikTok and analyse some popular brands in the space… are they being intentional? Possibly not.)

The citrus dilemma

Cheeky seems like a really good product. But what you wouldn’t get from the fun packaging is how darn hard it’s been to stay committed to a certain level of quality – like, for example, not including preservatives.

“The one that I do feel very conflicted about is the citrus because there's oxidation… heat and light change citrus. And so that's one where we could improve the consistency over time if we did a cold fill and added preservatives. But then again, I think the trade who uses it now might not be able to use it if we did that.”

April leans straight into the conflict. She is aware it’s challenging and does not claim to know all the answers. She is sitting back, observing, and will move when the right path is clear.

What drives her is not just the market opportunity but, as she puts it, being “the type of person who can build a massively successful brand and have all of the learnings that accompany that.”

The secret to succeeding in today’s market? Is it AI? Is it??

This is really interesting. I asked April what she thinks it will take for brands to make it in today’s climate – and she brought up how she’s used AI to learn about and improve ad performance.

“I never ran a Meta ad. Well, that’s not true. I tried to run Meta ads very unsuccessfully before and I just went in two weeks from 0% click-through rate to, on the high end, 20 almost 24% click-through rate on some of my cold prospecting ads.”

Her takeaway: “It’s never been easier to start a brand, really hard to grow a brand, and really hard to grow a brand to any like significant size.”

I told her I felt the same: we don’t know what the next three years of brand building look like, but the founders who learn fastest will be the ones to survive.

It would suck to fail but she’s willing to take the risk

April is building something that feels premium without being precious; respected by bartenders but approachable for everyone else. And she’s doing it with full awareness of how hard the game is. “It would suck to fail. It would really, really suck to fail,” she told me, “but I want the satisfaction of building something that can stand on its own feet.”

“It would suck to fail. It would really, really suck to fail. But I want the satisfaction of building something that can stand on its own feet.”

Most founders try to polish away that risk. April names it outright. She’s willing to admit the fear and go for it anyway. In a market where starting is easy and growing is brutal, that hunger for the fight is a baseline, not a nice-to-have.