Alcohol as cultural technology: the 13,000-year case

My interview with author, professor, and philosopher Edward Slingerland on the evolution of trust and the magic of the short-circuited brain.

The conversation around alcohol is becoming increasingly weird. We’re told there is no safe level of consumption. We’re being coached to view our bodies as chemistry sets, to do everything we can to “increase longevity.”

There’s some truth to this, of course. But I’ve had this nagging feeling that to demonize alcohol completely, to announce that we as the “evolved generation” are “moving on” from this evolutionary hiccup, seems narrow minded. There must be a bigger story here, I’ve been thinking, alcohol and humanity are too closely entwined to simplify our entire relationship to alcohol to “toxin.”

And then I read the incredible book Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilization by Edward Slingerland.

I Highly recommend this book to everyone - those who love to drink, those who are 100% sober, and everything in between.

So I was elated when Edward Slingerland, author and Professor of Early Chinese Philosophy, agreed to speak to me for this very newsletter. Edward has a unique vantage point: he truly looks at a glass of wine or a neat pour of spirits through a 13,000-year lens. His work suggests that alcohol isn’t an evolutionary mistake, but a cultural technology that actually made the human project possible.

We sat down to talk about the prefrontal cortex, the Southern way of drinking, and why a THC gummy is a terrible social tool (please forgive me, THC people).

The paradox of spontaneity

Edward’s journey into the history of booze started with ancient Chinese philosophy, specifically the concept of spontaneity. Spontaneity is a paradox. You cannot consciously try to relax, because the part of the brain you use to try, the prefrontal cortex (PFC), is the exact part that needs to shut down for you to be present.

The PFC is the center of our adult selves. It’s responsible for delayed gratification, staying on task, and spreadsheets. But it’s also the center of our inhibitions. To get around this, humans developed a chemical short circuit. Edward explains that “the wine goes in and turns down our prefrontal cortex for us. So it avoids this paradox of activating the part of the brain you’re trying to shut down.”

Alcohol downregulates the PFC, returning us to a child-like state of lateral thinking where we can connect ideas that don’t seem related and, more importantly, trust the people sitting across from us.

Ever become friends with someone when drinking that you normally don’t talk to? I sure have. That’s the magic. It takes down the barriers.

The sandbox of the mind

One of Edward’s most compelling points is about the adult brain being the enemy of innovation. Children are naturally creative because their PFC isn’t fully developed yet; they can see a cardboard box and truly believe it’s a spaceship. If I tell my 5-year-old that her breakfast is “kitty food” she’ll be much more likely to eat it (while meowing). As adults, our PFC “knows” it’s just a box or a bowl of oatmeal.

By temporarily handicapping the PFC, alcohol allows us to return to a state of cognitive flexibility. For a founder or a creator, a drink isn’t an escape from work; it’s a tool to bypass the internal critic that kills new ideas.

Edward notes that: “one function of alcohol is to temporarily turn the PFC down and return us to being more like we were when we were kids before we had fully developed PFCs and we’re flexible and we see possibilities.”

This allows the brain to play in a sandbox that the adult PFC usually keeps locked. Because humans are an “intensely tool-dependent, technology-dependent species,” we are “completely dependent on creativity for our success.”

The dishonesty premium and social trust

The current wellness movement often frames drinking as unevolved. Edward argues that by focusing solely on the physical cost, we are ignoring the catastrophic cost of the alternative: loneliness and a lack of social trust.

Lying is a very PFC heavy function. It takes a lot of cognitive energy to maintain a deception. When we drink together, we are essentially cognitively disarming. Edward describes the act of sharing a drink as a high stakes social signal: “If we sit down and have a couple beers, I’ve taken my PFC out and put it on the table and said, ‘I’m cognitively disarmed. I’m going to have trouble lying to you.’”

It’s the modern version of shaking hands to show you aren’t holding a weapon; you’re showing the other person that you are currently incapable of complex manipulation. This disarming is what allowed humans to move from small tribes to massive, innovative civilizations. It creates a state where trust can move faster than it ever could in a purely sober, guarded environment.

Respecting the potency of the liquid

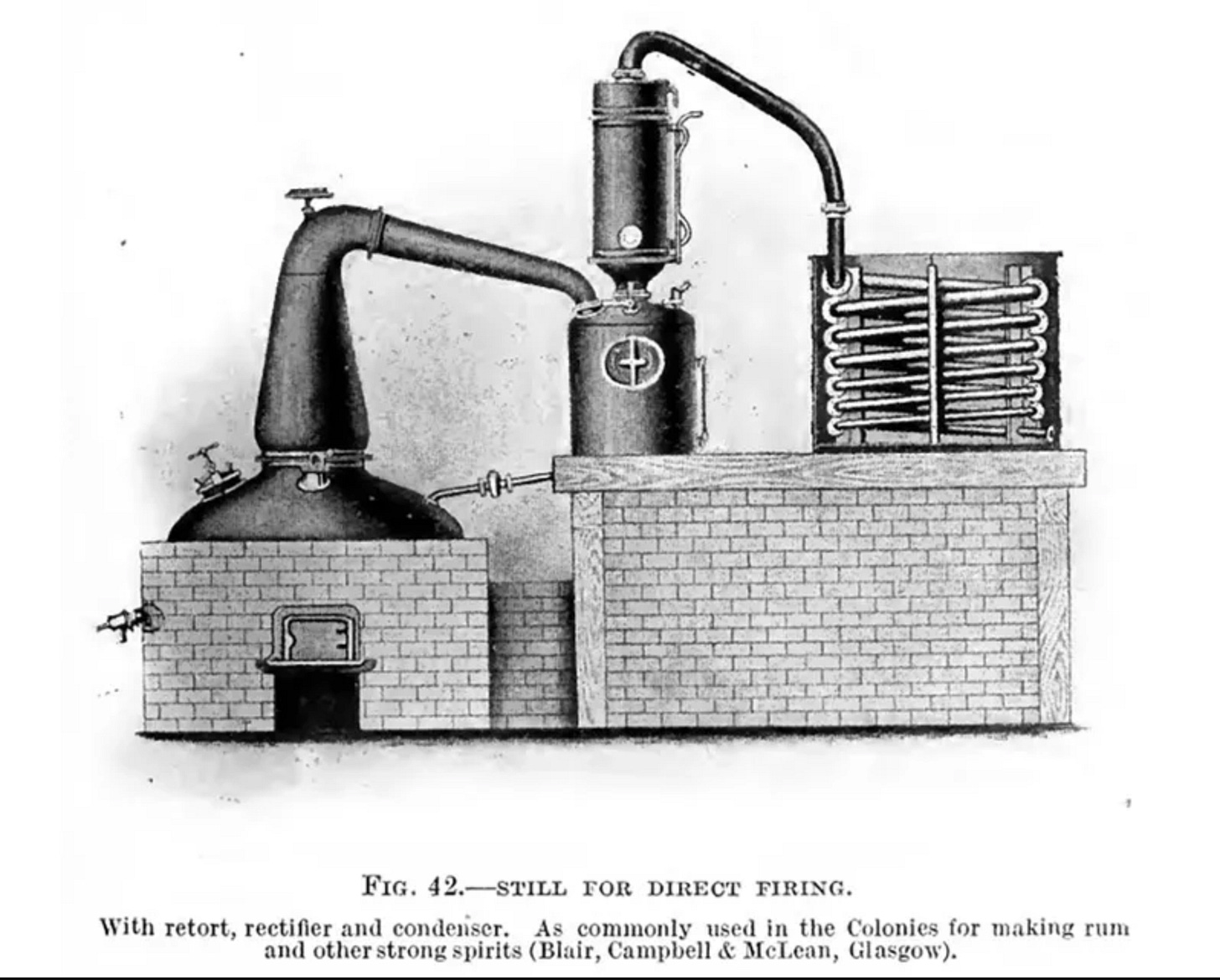

For most of history, humans were limited by natural fermentation, which usually caps out around 2 or 3 percent ABV. Edward points out that the arrival of distillation changed the landscape. It created a super concentrated, high potency version of ethanol that requires a higher degree of care.

The shift today isn’t about running away from spirits. It is about bringing back the ritual that these stronger liquids demand. Because spirits are so much more potent than the weak beer of our ancestors, they can’t be treated casually. Edward warns that “it’s in such a concentrated form that I think you should really think about it as a different type of drug and treat it that way.”

The danger is really the loss of the social mandate and pacing. We’ve moved from the public square to the private home. When we take a concentrated substance and use it in isolation, we lose the brakes provided by the group.

The Southern vs. Northern model

Edward draws a sharp distinction between how different cultures handle the beast of alcohol.

The Northern Model: Alcohol is a separate event. You go to a bar specifically to get drunk. It’s often about escape or blowing off steam.

The Southern Model: Alcohol is a background character. It is integrated into the table, consumed in moderation, and almost always paired with food and mixed generational groups.

In Italy, historically, they drank the most per capita, but they had some of the lowest alcoholism rates in the world. In the Southern model, visible drunkenness is a source of social shame. Edward argues that “adopting something like the Southern drinking culture is probably protective” against the risks of alcohol use disorder. It’s a more sophisticated way of engaging with the liquid, treating the drink as a catalyst for conversation rather than the destination itself.

Why the green wave will never replace the bar

With the rise of legal cannabis, many predict the end of the spirits industry. Edward is skeptical. From a cultural evolutionary standpoint, cannabis lost the battle to ethanol thousands of years ago for a reason: it’s a bad social drug.

Cannabis lasts too long, it’s difficult to dose, and it often makes people paranoid or inside their own heads rather than socially bonded. “Cannabis will never replace alcohol for this reason,” Edward says.

He notes that for many, “it [cannabis] makes us really paranoid... it’s a really s*** social drug for us” compared to the predictable, short lived, and talkative nature of alcohol.

Alcohol won because it is predictable, its effects are short lived, and it consistently makes people want to talk to each other.

Reclaiming the connection

As we look toward 2026, the brands that win won’t be the ones selling wasted nights or pure optimization. They will be the ones that help us reclaim the Southern model of connection. That help people connect with the real tangible benefits of alcohol.

Alcohol, when treated with the care its potency deserves, serves as a catalyst for our social lives. It’s a tool that helps us put down our phones, turn off our internal spreadsheets, and actually see the people in front of us.

The takeaway for founders: Don’t sell the liquid; sell the container. And alcohol isn’t going anywhere. It’s too much a part of who we are.

THE NEW RULE:

The goal isn’t to defend drinking at all costs; it’s to defend the social life it makes possible. If your brand doesn’t help build the table, you’re just selling a commodity. If it does, you may be selling a lifeline.

The New Rules is a labor of love by nihilo.agency

Support us by:

- Subscribing

- Sharing

- Partnering with us

- Inviting us to speak at your conference or event on branding/bev/alc/fun